![]() The translation of the Tantrāloka

The translation of the Tantrāloka

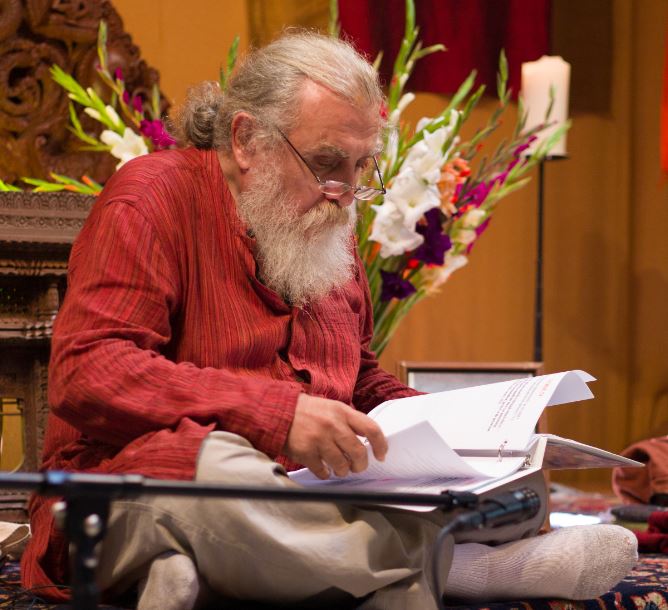

We are thrilled to announce that after 45 years of the spiritual, intellectual, and human labour of Mark Dyczkowski, his translation of the Tantrāloka has been completed. There are eleven volumes contains the thirty-seven chapters of the Tantrāloka. An introduction being prepared and another volume dedicated to the cross referencing and exposition of Abhinavagupta’s sources. The eleven volumes contain a full, minutely accurate translation of both Abhinavagupta’s great work and the commentary by Jayaratha that must be read together with it. Mark Dyczkowski has worked directly with manuscripts and so has had occasion to make improvements to the published edition in Sanskrit. He has collected all the known unpublished sources Abhinavagupta quotes that have been recovered in the past decades. The translation is furnished with extensive and very detailed notes drawn from the works of the great Kashmiri masters themselves. He also draws from Swami Laksmanjoo’s teachings. The understanding of Swamiji’s revelation of the Tantrāloka, which is now also in the course of publication, is much enhanced by reading it along with this translation and, so too vice versa. There have been several translations in English, Italian, French and Hindi of all or part of the Tantrāloka. Mark has consulted all of them even though none of them are as accurate, extensively annotated and supported by decades of research of the unpublished source materials and those already published. Great care has been taken to maintain the most rigorous standards of modern scholarship. As such, the format precluded detailed discussion of practice. This shortcoming has been compensated by the hundreds of hours of lectures that can be downloaded from this site. The written text – one could say our basic Anuttara Trika scripture – is in this way sustained by the teachings of its direct practical application. Put simply, the lectures explain what the text in its own elevated manner, set in accord with the norms of an Indian technical treatise – śāstra, implicitly teaches concerning the practices of Trika Śaivism.

May it benefit all, with Śiva’s grace and Swami Lakshmanjoo’s blessings.

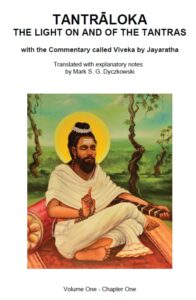

Tantrāloka – The Light on and of the Tantras

Chapter one is an introduction to the whole Tantrāloka and is concerned with an exposition of the fundamental basis of all practice, namely, transformative insight with devout reverence of our true Śiva nature. It presents the basic categories of practice and so an overview of all the Tantrāloka as the essence of Trika scripture which encompasses all the schools of early Tantric Śaivism. (Content Volume One)

Tantrāloka – The Light on and of the Tantras

Volume Two – Chapters Two and Three

Volume two begins with a brief chapter on the realisation of our true liberated nature in a flash of enlightenment, Chapter three is a beautiful and profound exposition of the fifty forms of reflective awareness of that reality symbolized by the succession of the letters of the alphabet that constitute the supreme subjectivity of Deity as AHAṂ – the great ‘I am’. (Content Volume Two)

Tantrāloka – The Light on and of the Tantras

Volume three is chapter four of the Tantrāloka. Its cardinal feature is an exposition of the Twelve Kālīs. The earliest sources of these teachings, called amongst other things, Mahānaya or Mahārtha, recovered from unpublished manuscripts are presented in extensive appendices. These have never been published before. The texts are as profound as they are thrilling beautiful. (Content Volume Three)

Tantrāloka – The Light on and of the Tantras

Volume Four – Chapters Five and Six

Volume four contains chapters five and six. Chapter five is a brilliant and astonishingly beautiful exposition of the types of practices listed in our primary scripture, the Mālinīvijayottara as those of the Corporeal Means (āṇavopāya). The following chapter is of great interest to the millions who practice attention to the flow of the cycle of breath. This is called the Wheel of Time (kālacakra). Here, drawing mostly from the Svacchandatantra, Abhinavagupta expounds how all the cycles of time are experienced within it. Freedom Cole, a well-known and most learned astrologer, has graced this volume with a beautiful, learned and detailed presentation of the astrology related to this practice. I most gratefully acknowledge him not only for what he has written but also for the many drawings and diagrams that adorn and clarify his exposition. (Content Volume Four)

Tantrāloka – The Light on and of the Tantras

Volume Five – Chapters Seven and Eight

Volume five of the translation of the Tantrāloka contains chapter seven and eight. Chapter seven called the Emergence of the Cycles of Mantras (cakrodaya) outlines in just seventy verses how Mantras and Vidyās of progressively increasing lengths are accommodated into the breathing cycle which increases proportionately. Having thus concluded the Path of Time, Abhinavagupta continues in chapter eight to teach the Path of Space. Drawing mostly from the Svacchandatantra he describes the 224 worlds and their inhabitants distributed in the thirty-six reality levels (tattva) from Earth to Śiva. Thus, he and Jayaratha together present the amazing richness and variety of the Śaiva cosmos and beyond. (Content Volume Five)

Tantrāloka – The Light on and of the Tantras

Volume Six – Chapters Nine and Ten

Volume six comprises chapters nine and ten of the Tantrāloka. In chapter nine Abhinavagupta expounds in detail the thirty-six reality levels (tattva) as taught by Śaivasiddhānta, modified by Pratyabhijñā and completed by the Trika. This is the most complete exposition of this important subject found anywhere. In the following chapter, Abhinavagupta presents the seven levels of perceivers arranged in a hierarchy along the ladder of the reality levels. Rising from the fully conditioned perceiver to Śiva they traverse the states of consciousness in consonance with the cycles of perception that Abhinavagupta describes in depth. (Content Volume Six)

Tantrāloka – The Light on and of the Tantras

Volume Seven – Chapters Eleven through Fourteen

Volume seven begins with chapter eleven and ends with fourteen. In chapter eleven Abhinava presents the five spheres of energies (kalā) and so completes the account of the first three Paths encompassing the realities that are the objects of denotation (vācya) to be purified (śodhya) (i.e., made one with consciousness), beginning with that of the worlds in chapter eight and the reality levels and their perceivers in chapters nine and ten. After briefly referring to the manner in which the Paths may be variously divided, Abhinava goes on relate the three Paths understood to be the spheres of objectivity, perception and the perceiver, with that of the phonemes (varṇa) as the energies of pure cognitive consciousness that represent the essence of the Paths of Mantra and its Parts, that together with the phonemes are the Paths of the denotators (vācaka) and purifiers (śodhaka). He goes on to discuss how phonemic consciousness is the ground of language, the aesthetic delight it evokes and the power that purifies the six-fold Path in and through perception. As usual, Abhinava concludes by explaining how everything is sustained within consciousness, he does it in this case by relating the two groups of Paths to one another as the sustained are to their sustainer, as is an image in a mirror or something seen in a dream to the dreamer. Śiva sustains and makes all things manifest within himself in this way.

Chapter twelve teaches the application of the Path to fashion the cosmic body and how all things – deities, Paths, Time and Space – are one within it. Internal Kaula worship consists of making offerings to them, free of doubts and inhibitions.

In chapter thirteen Abhinava goes on talk about Śiva’s grace in accord with the teachings of his Trika master Śambhunātha. He deals with the basic concepts and problems regarding the descent Śiva’s power of grace (śaktipāta). The highest grace is the liberation attained by the realization of one’s own unconditioned Śiva nature as the ultimate nature and source of all things. This takes place when Karma comes to an end. Abhinava tackles the main questions in relation to this doctrine to establish that Śiva is free to grace whoever he chooses whenever he likes. Although he agrees with the Siddhāntin that the occasion for this purifying grace is initiation, he refutes his view that it takes place when the postulant’s good and bad Karmas balance out or binding impurity ‘matures’ enough to be removed. If the occasions for grace where to be such, Śiva would be constrained to wait for them to arise. This, Abhinava points out, would imply that he is not free to act as he wishes and would be as constrained by causes and conditions as is any fettered soul. For Śiva to be Śiva, that is, free, complete and unconditioned, he cannot be confronted with some other alien reality that could limit him. Thus, ultimately, we must admit that it is Śiva who both illumines and obscures himself.

Abhinava then goes on to talk about the varieties of the descent of grace (129cd-132) and how they are distinguished from one another by the degree of the capacity for insight (pratibhā) they evoke. This leads him to outline a hierarchy of teachers based on the degree of the power of intuition (pratibhā) they possess (132cd-139) and to discuss its nature and how it operates (142-187ab). (Content Volume Seven)

Tantrāloka – The Light on and of the Tantras

Volume Eight – Chapter Fifteen

Volume Eight is chapter fifteen of the Tantrāloka, which is largely drawn from chapter eight of the Mālinīvijayottara, which Abhinava reproduces entirely and comments on it in great detail. It is especially important as it presents the rite of initiation to the basic condition of a Trika Śaiva, that is, as one who has vowed to observe the pledges (samaya). Serving first as the purifying rite of initiation, the initiate continues to perform a modified form of the rite on a regular (nitya) daily basis. The focus is on the worship of the triadic deity of the Trika, namely, the goddesses Parā, Parāparā and Aparā who are seated on their Bhairavas in lotuses situated on the prongs of the Trika Trident. From the bulb at the base of the Trident, to the tips of its prongs, it extends for all the thirty-six reality levels and beyond into the thirty-seventh, which is Supreme Śiva otherwise known as Supreme Bhairava upon. The Goddess Kālasaṃkarṣiṇī as the thirty-eighth is the Inexplicable, the highest reality of all. Worshipped externally in the maṇḍala and inwardly in the subtle body, the Vidyās and Mantras of the Trident that mark the ascent through it and the worship of the deities and their attendants on it, are collected together in the appendix of this volume. The chapter concludes with a presentation of the pledges taught in a series of major Trika, Krama and Bhairava Tantras. (Content Volume Eight)

Tantrāloka – The Light on and of the TantrasVolume

Nine – Chapters Sixteen through Twenty-seven

Volume nine contains chapters sixteen to twenty-seven. It begins with an exposition of the initiation into the condition of a teacher’s apprentice (putraka) that can lead to his consecration as a teacher and priest (ācārya). Whereas the basic (samaya) initiation is performed with a single Trident maṇḍala, the power of this higher one is strongly reinforced by the worship of three triads and the incorporation of the worship of the Twelve Kālīs, surrounding the calyx of the lotus in the centre. An interesting passage concerning animal sacrifice follows. Omitted at the first level, here, in order to progress to the level of a teacher and priest, it is an essential requirement. The rest of the initiation involves the complex projection (nyāsa) of layers of Mantras, beginning with those of the Six Paths, onto the neophant’s body and the sacrificial area.

Chapter seventeen continues with a series of procedures concerning the apprentice beginning with the fashioning of his sacred thread and the purification of the reality levels he is to traverse in the course of initiation. It continues with the inner illumination of his body with Mantra, the burning away of his fetters, his conjunction to the supreme principle and offerings to the fire.

The following nine chapters are quite short and deal with specific initiations. Chapter eighteen is just a few verses outlining the brief initiation (sūkṣmā dīkṣā). Chapter nineteen teaches the initiation that takes place at the moment of death (utkrānti) and the manner of reciting the Brahmā Vidyā to someone at the time of death to liberate him or her. Chapter twenty teaches a peculiar initiation that is validated by measuring the loss of weight that is believed to occur due to the burning away of the neophant’s impurities. Twenty-one deals with the initiation of those who are absent and twenty-two with the rite by which a Vaiṣṇava is converted to a Śaivite. Twenty-three is concerned with the consecration of a teacher and twenty-four deals with an initiate’s funerary rites. Chapter twenty-five deals with the offerings to the ancestors, twenty-six, the remaining observances after initiation until death and twenty-seven, the worship of Liṇgas. (Content Volume Nine)

Tantrāloka – The Light on and of the Tantras

Volume Ten – Chapters Twenty- eight and Twenty-nine

Volume ten contains the following two chapters. The previous chapters from fifteen onwards were concerned with obligatory (nitya) rites for those who belong or wish to belong to the Trika Śaiva tradition. The rites that follow from here onwards are occasional (nimittika) in the sense that they only take place at certain times in particular circumstances such as festivals and days of atonement. Accordingly, the first part of chapter twenty-eight (up to verse 59) is concerned with listing these sacred times (parvan) and the rites that are performed then. Foremost amongst them, are those that take place on the occasions when initiates and their teachers assemble to worship together (60cd-111). This is called Aadiyāga – the Foremost Sacrifice, which Abhinava stresses is considered to be the most elevated by the Trika Tantras. Abhinava goes on to outline the manner of crafting and offering of a sacred thread to the deity as a rite of atonement (112-186ab) and other occasional rites (186cd-212) such as the celebrations of the teacher’s birth and death day (213-216). This is followed by a series of rites and yogic practices related to the moment of voluntary death, the spiritual status of the initiate at that time as well as places and occasions for it to take place (217-367). After briefly returning to the rites concerning the assembly of Yoginīs and initiates, the chapter ends with the procedures for the explanation of the scriptures (vyākhyāvidhiḥ) (385cd-407), the expiation of transgressions (408-423ab) and the worship of the teacher (gurupūjāvidhi) (423cd-435).

Chapter twenty-nine is notorious for teaching Kaula ritual involving the offering of meat, wine and sexual fluids to the Goddess (kaulikīśakti), alone (ekavīrā) or with her partner in union (yāmalabhāva). The rites presented up to chapter twenty-eight are largely in the Tantric modality (tantraprakriyā), those that follow are predominantly in the Kaula one (kulaprakriyā). Such is the rite of chapter twenty-nine which is essentially an elaboration of the Aadiyāga (also called Aadyayāga) – Foremost Sacrifice – taught in the Mādhavakula section of the Jayadrathayāmala. After an initial exposition of the essential elements of Kaula ritual, he goes on to present the regular, basic Kaula rite. This is drawn from both Trika Kaula and Krama Kaula sources. This begins with the outer rite which is heralded by the worship of the Kulamaṇḍala into which the Gurumaṇḍala is incorporated (24-81) and is followed by the repetition of Mantra (82-95). After that comes the sexual rite performed with a Tantric consort (dautavidhi). Once outlined the qualities she should possesses (97-115ab), Abhinava goes on to expound the inner events that take place within consciousness in the course of union with her according to his personal insight. By the outer ritual consumption of the ejaculate as taught in the Mādhavakula, the rite reaches its conclusion (96-186ab).

Abhinava goes on to explain the foundation upon which the rite is grounded and renders the participants fit to perform it in a long section dedicated to the forms of Kaula initiations ranging from the basic one to the consecration of a teacher (187cd-235). The Tantric modality is centred on the journey of along the six-fold Path, the Kaula on a corresponding series of six ways of piercing (vedha) through the inner centres of the Kaula body (236-281) as taught in the Kulagahvara and the Vīrāvalikula. (Content Volume Ten)

Tantrāloka – The Light on and of the Tantras

Volume Eleven – Chapters Thirty through Thirty-Seven

Volume eleven contains the concluding chapters thirty to thirty-seven. Chapter thirty is a concise compendium of the Mantras used for the main rites taught in the Tantrāloka. At the beginning and end a few verses are dedicated to the fundamental metaphysical nature of Mantra and their inner vitality (1-4, 121cd-123) as consciousness to insure, as always, an abiding awareness that they are grounded in it. Abhinava presents the Mantras according to their order of importance beginning with the Trident Throne and the deities seated on it (5-43ab). He continues with a series of Krama Vidyās (45cd-55ab), Mantras uttered at the time of death to induce it and liberate dying man (55cd-92), those for the Scale Initiation (91cd-98), the Sacrificial Animal (91cd-92), a Mantra to paralyze witches (Śākinīs) (93-94ab), Bhairava’s Heart Mantra (94cd-99), the Mantra for the initiation taught in the Śrīsantati 100-101, and the three Vidyās (102-121ab)

In chapter thirty-one Abhinava presents ways to draw varieties of Trika Trident maṇḍalas taught in as many Trika Tantras beginning with the Mālinīvijayottara.

Chapter thirty-two is dedicated to mudrās. As with the Mantras, Abhinava begins with a presentation of their essential nature (1-10ab) and concludes with their vitality (vīrya) (63-65) Of the many mudrās, the highest is Khecarīmudrā– the Seal of the Skyfaring Goddess of which six varieties are taught drawn from mostly, if not entirely, Trika Tantras.

Chapter thirty-three completes the standard set of four categories – Vidyā, Maṇḍala, Mudrā and Mantra. Here Abhinava lists the 174 members of the assemblies of Yoginīs (6, 12 + 12 + 16 = 46), power-holders (6 + 12+ 16 + 24 + 34 = 90) and Mantras (6 + 32 = 38) listed in the Mālinīvijayottara. Some of these groupings are mentioned in the context of various procedures, particularly in chapters sixteen and seventeen. They are all contained in the three Trika Goddesses and the Mātṛsadbhāva Vidyā of the Krama and, as derivatives of the primary alphabet energies, they are activities of consciousness. (20-32).

Chapter thirty-four teaches how to enter into one’s own nature (svasvarūpe praveśaḥ) by ascending through the Individual, Empowered, Śāmbhava states and beyond (1-4ab). This practice he tells us was taught by Sumati, who was Śambhunātha’s Trika teacher. This is evidence that the system of classifying practice into types of means (upāyabheda) formulated by Abhinava was originally formulated by his Trika teachers.

In chapter thirty-five Abhinava aptly concludes his exposition of Trika Śaivism by expounding the doctrine that all scripture is grounded in consciousness by way of the a priori certainty that is the foundation of all knowledge. Devoid of this certainty, no knowledge could be valid in itself and so would require another cognitive act to confirm it, leading to an infinite regress. This a priori certainty (prasiddhi) is the ground of all daily life, no less than the transmission of scripture and its validity. Following the lead of his Trika teacher Śambhunātha, Abhinava affirms that this certainty is the essence of Trika and is essentially what it is. Thus, all the Śaiva scriptures ranging from the Veda and culminating in Trika are like the fruits clinging to the great vine of that spiritual fundamental common belief and certainty (prasiddhi).

Chapter thirty-six is dedicated to outlining the steps in the transmission of the Siddhayogīśvarīmata initially from Bhairava to Bhairavī and then down in successively shorter versions until Rāma obtained it from Vibhīṣaṇa, Rāvaṇa’s brother, who transmitted it to him by word of mouth (1-6). After listing its parts, Abhinava declares that the Tantrāloka is the essence of the three and a half Śaiva orders (maṭhika) that have descended from Śrīkaṇṭha through Amardaka (dualist), Śrīnātha (dualist-cum-non-dualist), Tryambika (non-dualist) and his daughter who taught Trika (11-14).

Chapter thirty-seven opens with Abhinava’s final overview of the types of scriptures, the basis of their hierarchy and how Trika Kaulism is their most excellent teaching because it is transmitted in a flash of immediate realization (1-29) Abhinava concludes his work (30-85) with a brief biography of his ancestors. This is prefaced by a eulogy of the spiritual power and beauty of India, the Land of Kumārikā and especially of Madhyadeśa – the Middle Land. The heart of modern Uttar Pradesh, its capital was Prayāga, modern Allahbad. This was the home of his learned ancestor Atrigupta whom king Lalitāditya (c 724-760) brought to Kashmir (33-40). Abhinava goes on to extol the beauty of the Kashmir Valley and the greatness of its inhabitants. He lauds king Pravarasena (c. 530-590) who founded the capital Pravarapura (nowadays called Srinagar) through which the beautiful, sacred river Vitasta flows (41-51). The rest is dedicated to Abhinava himself, his family and those around him. His ancestral home in Pravarapura donated to Atrigupta was handed down to Varāhagupta and then to his father Narasiṃhagupta (52-54) He goes on to describe his grief at his mother’s demise in his childhood. He refers to a period of worldly enjoyment in his youth and the dawning of discrimination (55-57). He extols his spiritual and learned father as his first teacher (58-59) and goes on to supply a list of his teachers first (60-63) and then his students. Amongst the latter he refers to his brother Manoratha (64-72) whom he much admired for his devotion to the study of scriptures and the worship of Lord Śiva. He praises his dear sister Ambā who served and venerated him as a veritable embodiment of Lord Śiva. (76-80). Like his ancestors, Abhinava’s close friends and supporters were government officials. Foremost amongst them was the minister Śauri. He invited him to live in his country estate where he and his wife Vatsalikā took care of him (73-75). It was there that, assisted by his secretary Lumpaka, he wrote the Tantrāloka (81-82). After this short and deeply human biography he ends his great work with a blessing and a prayer saying of himself:

(Thus), he composed this greatly precious (mahārtha) work, in which is expounded the essence of the Tantras (tantratattva), in accord with reason (yukti) and the tradition (āgama). Easy is the practice of (their) rites once (the people of) this world has acquired (its) light (āloka). May you (who are) good receive well (anugṛh) this, his work, but first of all seek to grasp it (grḥ). This is the rule. And may that also lay hold (gṛh) of your mind and soon grace it (anugṛh) by the vision of the reality (it bestows).

O Śiva, you who hear (everything) in all respects, listen (graciously) to this essence of the scriptures, composed by Abhinavagupta. This, in truth, is praise (nuti) (dedicated) to You; and, indeed, it is an examination of your nature. (O Lord,) satisfied by (this) praise (abhinava), make the (whole) world one with Yourself! TĀ 37/82-85 (Content Volume Eleven)

“This work comes as the fruit of a lifetime of hard work, study and practice, and my prayer to Lord Śiva, the Mother and my master Swami Laksmanjoo is that it will be of benefit to others as it has benefitted me.”

Mark Dyczkowski